Ricerca Veloce

Ricerca Avanzata

chiudi

One has a name that is a household word. The other is known mostly by fashion’s cognoscenti. But the collaboration between Giorgio Armani

One has a name that is a household word. The other is known mostly by fashion’s cognoscenti.

But the collaboration between Giorgio Armani and the photographer Aldo Fallai in the 1980s is more than just a record of a powerful artistic relationship. It shows the essence of Armani as a designer and how the image that the designer created in his mind and in cloth was translated for the wider world.

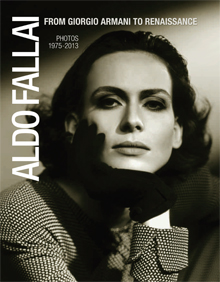

The exhibition “Aldo Fallai, From Giorgio Armani to Renaissance, Photos 1975-2013” through March 16 at the Villa Bardini in Florence and the accompanying book should be viewed as an object lesson in style for any aspiring designer.

Mr. Fallai captures so boldly — yet with great subtlety — what Mr. Armani understood: That the androgynous 1980s were more than skin and pantsuit deep.

Their spontaneous alliance created a vision of a new woman and a newly softened male. The Armani clothes freed the wearer from all restraints, giving the same possibility of an energetic life to both sexes. Above all, the duo captured a new female attitude: She could dare to present herself as an intelligent adult, whether you call an oversize pantsuit, ironing out curves, unisex or androgynous.

The female models were mostly jolie laide, the French term for “pretty-ugly.” But their faces are filled with character, which after the “dolly girls” of the 1960s and the skinny creatures with weeping hair in the 1970s, was a minor revolution.

A firm female figure, clasping daily newspapers to her wide-shouldered suit, expressed absolutely who was kicking out the glass ceiling back in 1984. Her counterpart by 1993 was a man, denim jacket tied around the waist below a bared chest, clutching an armful of flowers.

Many of Mr. Fallai’s images were for the less expensive Emporio Armani line. They included families, so children with a solemn stare or a man walking along, holding a child’s hand, suggested major societal shifts.

Mr. Fallai, working, of course, before the digital era, still managed to convince the viewer that his bold woman, standing at the water’s edge, was at Portofino or some other iconic Italian beach. In fact, at the exhibition opening, he re-lived the moment when he hoisted a blown-up image of the backdrop onto a wall so the photography would capture the right spirit.

In that era, long before today’s post-production “improving” of images, there is a frankness to the photographer’s work that penetrates the mind.

Even more recent studies — people of today presented as Renaissance figures — have the same raw simplicity. The faces and the clenched hands are presented warts and all.

But it is the Armani pictures that offer such insight into both a period and a time when capturing a style was a collaboration between designer and photographer, rather than a team of professional brand-builders.

As a great designer, Mr. Armani produced work that proves something else. Although the clothes were revolutionary in their time, they have grown into classics. Maybe the androgyny of the 1980s now seems a little forced, but this was a period when making a female pantsuit elegant was a revolution.

The male, of course, appears in similar studies. The ease with which cloth folds over the male torso is another of Mr. Armani’s skills. And Mr. Fallai shows figures of sweet gentility, while at the same time making them distinctly male.

It is rare to see a collaboration that so captures a moment, nor an exhibition with such a clear purpose.

The show, although perhaps at its most beautiful in the Bardini museum with its hilltop view over Florence, deserves to travel the world as a celebration of art — both from photographer and designer.

But the collaboration between Giorgio Armani and the photographer Aldo Fallai in the 1980s is more than just a record of a powerful artistic relationship. It shows the essence of Armani as a designer and how the image that the designer created in his mind and in cloth was translated for the wider world.

The exhibition “Aldo Fallai, From Giorgio Armani to Renaissance, Photos 1975-2013” through March 16 at the Villa Bardini in Florence and the accompanying book should be viewed as an object lesson in style for any aspiring designer.

Mr. Fallai captures so boldly — yet with great subtlety — what Mr. Armani understood: That the androgynous 1980s were more than skin and pantsuit deep.

Their spontaneous alliance created a vision of a new woman and a newly softened male. The Armani clothes freed the wearer from all restraints, giving the same possibility of an energetic life to both sexes. Above all, the duo captured a new female attitude: She could dare to present herself as an intelligent adult, whether you call an oversize pantsuit, ironing out curves, unisex or androgynous.

The female models were mostly jolie laide, the French term for “pretty-ugly.” But their faces are filled with character, which after the “dolly girls” of the 1960s and the skinny creatures with weeping hair in the 1970s, was a minor revolution.

A firm female figure, clasping daily newspapers to her wide-shouldered suit, expressed absolutely who was kicking out the glass ceiling back in 1984. Her counterpart by 1993 was a man, denim jacket tied around the waist below a bared chest, clutching an armful of flowers.

Many of Mr. Fallai’s images were for the less expensive Emporio Armani line. They included families, so children with a solemn stare or a man walking along, holding a child’s hand, suggested major societal shifts.

Mr. Fallai, working, of course, before the digital era, still managed to convince the viewer that his bold woman, standing at the water’s edge, was at Portofino or some other iconic Italian beach. In fact, at the exhibition opening, he re-lived the moment when he hoisted a blown-up image of the backdrop onto a wall so the photography would capture the right spirit.

In that era, long before today’s post-production “improving” of images, there is a frankness to the photographer’s work that penetrates the mind.

Even more recent studies — people of today presented as Renaissance figures — have the same raw simplicity. The faces and the clenched hands are presented warts and all.

But it is the Armani pictures that offer such insight into both a period and a time when capturing a style was a collaboration between designer and photographer, rather than a team of professional brand-builders.

As a great designer, Mr. Armani produced work that proves something else. Although the clothes were revolutionary in their time, they have grown into classics. Maybe the androgyny of the 1980s now seems a little forced, but this was a period when making a female pantsuit elegant was a revolution.

The male, of course, appears in similar studies. The ease with which cloth folds over the male torso is another of Mr. Armani’s skills. And Mr. Fallai shows figures of sweet gentility, while at the same time making them distinctly male.

It is rare to see a collaboration that so captures a moment, nor an exhibition with such a clear purpose.

The show, although perhaps at its most beautiful in the Bardini museum with its hilltop view over Florence, deserves to travel the world as a celebration of art — both from photographer and designer.

Data recensione: 13/01/2014

Testata Giornalistica: The New York Times

Autore: Suzy Menkes