Ricerca Veloce

Ricerca Avanzata

chiudi

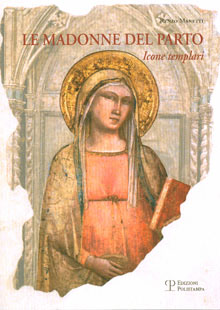

Un piccolo saggio edito da Polistampa di uno studioso di architettura e iconologia, Renzo Manetti, Le Madonne del Parto. Icone templari, che analizza le immagini delle

Italian author claims paintings are linked to suppression of Knights Templar

An Italian author has stirred controversy within the Roman Catholic church with a new theory linking one of the most intriguing traditions in western art to the suppression of the enigmatic Knights Templar. A string of artists working from the middle of the 14th century near Florence painted the Virgin Mary as they imagined her to have been while she was pregnant. The best-known of these swelling Madonnas is by the great 15th century Tuscan artist Piero della Francesca. It shows an apparently dejected mother-to-be with one hand resting on the burgeoning front of her maternity gown. Piero della Francesca’s fresco, preserved in a cemetery chapel at Monterchi, near Arezzo, was not just the high point of the tradition. It virtually brought it to an end.

Carvings and sculptures of pregnant Marys have a longer history before and after the early Renaissance. But the painting of them by artists of stature is almost entirely confined to Tuscany in the 130 years ending around 1467, when Piero della Francesco is reckoned to have created the fresco at Monterchi. In a 40-page booklet published last month, Renzo Manetti, a Florentine architect and author of several works on symbolism in art, argues that this is no coincidence. “Florence was a major Templar centre and these Madonnas start to appear soon after the suppression of the knights in 1312,” he told the Guardian this week. The first by a celebrated artist is attributed to Taddeo Gaddi and dated to between 1334 and 1338. “In virgin and child paintings, the child symbolises wisdom, knowledge, truth. So what the pregnant Madonnas represent is a temporarily hidden truth,” Mr Manetti said. The Knights Templar were a military-religious order founded in the early 12th century to defend the kingdom the crusaders had carved out in the Holy Land. From modest beginnings, the order grew to wield immense political and financial power not only in the Holy Land, but also in Europe. Pope Clement V ordered its dissolution after a campaign to discredit the order which saw bogus confessions extracted by the use of often ferocious torture. Two years after the pope issued his decree, the last grand master of the Knights Templar was burned at the stake on an island in the Seine in front of Nôtre Dame cathedral.

Controversy still rages over what secret knowledge, if any, the surviving Templars and their lay associates preserved. The question surfaced most recently in Dan Brown’s best-selling novel The Da Vinci Code, where it is held to be evidence that Jesus and Mary Magdalene had children whose descendants have survived to the present. If that theory is to be believed, then Mr Manetti’s interpretation raises the issue of which Mary is being depicted by the creators of the pregnant Madonnas. Mr Manetti, a practising Catholic, dismisses The Da Vinci Code as “based on a complete misunderstanding” of early Christian writings. But with leading figures in the church denouncing The Da Vinci Code as subversive, sensitivity among clerics to anything that echoes its contents is acute. And Mr Manetti’s theory has run into vigorous criticism from the priest whose church in Florence houses Gaddi’s pregnant Virgin.

In a 15-page article due to appear soon in the diocesan periodical, Father Giovanni Alpigiano argues for the traditional view that the expectant virgins represent the theological concept of incarnation. There is “no arcane secret” attached to Gaddi’s Mary, he insists, despite her cryptic, knowing expression. “Great care needs to be taken in attempting to rewrite the history of art or literature solely with the help of esoteric clues,” Fr Alpigiano adds. An account of his counter-blast was splashed over the best part of a page in Avvenire, the national daily newspaper owned by the Italian bishops’ conference. Yet a prominent Catholic cleric, Monsignor Timothy Verdon, took part in the launch of Mr Manetti’s booklet. Mgr Verdon, the American-born canon of Florence cathedral, is a distinguished Renaissance scholar and the author of monographs on, among others, Piero della Francesca. “My own approach is that one should always look for the most universally accessible meaning,” he said yesterday. “Works of Christian art are meant to be understood by all-comers. But, that said, I find [Manetti’s] work interesting, stimulating. It puts one back in touch with a range of possibilities that might otherwise be forgotten.” Mr Manetti said: “I wouldn’t want to say that Piero and the other artists who painted the pregnant Madonnas were secret Templars, but they may well have been sympathisers”. Mr Manetti said there was evidence to suggest that a group of former warrior monks and their associates in Florence had founded a new order, of St. Jerome, which was generously endowed by rich Tuscan families who had previously been close to the Templars. As the dispute gathers momentum, one question remains so far unanswered. What does Mr Manetti believe was the true secret these great artists thought they were alluding to? Mr Manetti is not telling. But he will be publishing a full-length book on the subject later this year.

An Italian author has stirred controversy within the Roman Catholic church with a new theory linking one of the most intriguing traditions in western art to the suppression of the enigmatic Knights Templar. A string of artists working from the middle of the 14th century near Florence painted the Virgin Mary as they imagined her to have been while she was pregnant. The best-known of these swelling Madonnas is by the great 15th century Tuscan artist Piero della Francesca. It shows an apparently dejected mother-to-be with one hand resting on the burgeoning front of her maternity gown. Piero della Francesca’s fresco, preserved in a cemetery chapel at Monterchi, near Arezzo, was not just the high point of the tradition. It virtually brought it to an end.

Carvings and sculptures of pregnant Marys have a longer history before and after the early Renaissance. But the painting of them by artists of stature is almost entirely confined to Tuscany in the 130 years ending around 1467, when Piero della Francesco is reckoned to have created the fresco at Monterchi. In a 40-page booklet published last month, Renzo Manetti, a Florentine architect and author of several works on symbolism in art, argues that this is no coincidence. “Florence was a major Templar centre and these Madonnas start to appear soon after the suppression of the knights in 1312,” he told the Guardian this week. The first by a celebrated artist is attributed to Taddeo Gaddi and dated to between 1334 and 1338. “In virgin and child paintings, the child symbolises wisdom, knowledge, truth. So what the pregnant Madonnas represent is a temporarily hidden truth,” Mr Manetti said. The Knights Templar were a military-religious order founded in the early 12th century to defend the kingdom the crusaders had carved out in the Holy Land. From modest beginnings, the order grew to wield immense political and financial power not only in the Holy Land, but also in Europe. Pope Clement V ordered its dissolution after a campaign to discredit the order which saw bogus confessions extracted by the use of often ferocious torture. Two years after the pope issued his decree, the last grand master of the Knights Templar was burned at the stake on an island in the Seine in front of Nôtre Dame cathedral.

Controversy still rages over what secret knowledge, if any, the surviving Templars and their lay associates preserved. The question surfaced most recently in Dan Brown’s best-selling novel The Da Vinci Code, where it is held to be evidence that Jesus and Mary Magdalene had children whose descendants have survived to the present. If that theory is to be believed, then Mr Manetti’s interpretation raises the issue of which Mary is being depicted by the creators of the pregnant Madonnas. Mr Manetti, a practising Catholic, dismisses The Da Vinci Code as “based on a complete misunderstanding” of early Christian writings. But with leading figures in the church denouncing The Da Vinci Code as subversive, sensitivity among clerics to anything that echoes its contents is acute. And Mr Manetti’s theory has run into vigorous criticism from the priest whose church in Florence houses Gaddi’s pregnant Virgin.

In a 15-page article due to appear soon in the diocesan periodical, Father Giovanni Alpigiano argues for the traditional view that the expectant virgins represent the theological concept of incarnation. There is “no arcane secret” attached to Gaddi’s Mary, he insists, despite her cryptic, knowing expression. “Great care needs to be taken in attempting to rewrite the history of art or literature solely with the help of esoteric clues,” Fr Alpigiano adds. An account of his counter-blast was splashed over the best part of a page in Avvenire, the national daily newspaper owned by the Italian bishops’ conference. Yet a prominent Catholic cleric, Monsignor Timothy Verdon, took part in the launch of Mr Manetti’s booklet. Mgr Verdon, the American-born canon of Florence cathedral, is a distinguished Renaissance scholar and the author of monographs on, among others, Piero della Francesca. “My own approach is that one should always look for the most universally accessible meaning,” he said yesterday. “Works of Christian art are meant to be understood by all-comers. But, that said, I find [Manetti’s] work interesting, stimulating. It puts one back in touch with a range of possibilities that might otherwise be forgotten.” Mr Manetti said: “I wouldn’t want to say that Piero and the other artists who painted the pregnant Madonnas were secret Templars, but they may well have been sympathisers”. Mr Manetti said there was evidence to suggest that a group of former warrior monks and their associates in Florence had founded a new order, of St. Jerome, which was generously endowed by rich Tuscan families who had previously been close to the Templars. As the dispute gathers momentum, one question remains so far unanswered. What does Mr Manetti believe was the true secret these great artists thought they were alluding to? Mr Manetti is not telling. But he will be publishing a full-length book on the subject later this year.

Data recensione: 23/07/2005

Testata Giornalistica: The Guardian

Autore: John Hooper